In Tents

A ferrocerium rod is a man-made metallic stick producing hot sparks through friction with a striker, a synthetic flint with a brightly coloured end. More reliable than a gas filled lighter, it lasts longer and is more robust. A carbon blade lock-knife is a compact tool - safe and easy to transport, but sharp enough to deal with many outdoor tasks. A paracord survival bracelet is a long length of strong thick nylon string, wound and knotted into a wearable bangle used for fixing kit, lighting fires and stringing food between trees. Tactical survival gear.

These artefacts are not only highly practical but also function as talismans for protection from the elements: symbols of an association with the land, gestures of empowerment and self-sufficiency infused with the essence of simple, unencumbered living.

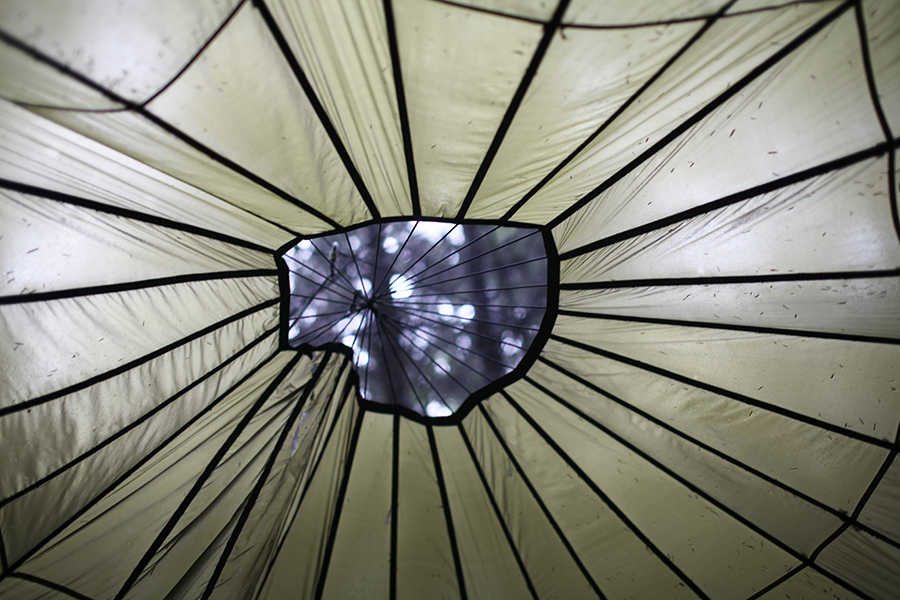

Camping is a basic DIY method for living simply outside but it is also in some ways a sport that embodies a tension between surviving and relaxing with one facilitating the other in a self perpetuating cycle of human endeavour. We find ourselves spinning a web with luminous guy ropes in order to feel a primeval connection with the ground, the earth’s rhythms and the ritual of fire lighting. An association with nature becomes mediated by synthetic, watertight, breathable neon or camouflage print, our safety ensured by high-tech-low-weight fabrics and gadgets. Often the precious time spent camping has been ‘earned’, gained and marked as leisure in order to practise survival.

Paraweb, installed in There Are No Firm Rules exhibition at Site Gallery, Sheffield, 2016

Camping in an urban environment has different meanings, it is more often associated with activism, protest movements and reclaiming the streets and city centres, a quick functional way to inhabit the city in another layer on top of the institutional municipal landscape and smashing through the pretence that it is impenetrable. Urban camping is also a necessity for those who reside in the city without a fixed abode, encampments of the most precarious kind are present in parks under bridges and in doorways, shelters of polythene and cardboard.

Exploring the remains of a 5000 year old village in Almería led me to feel that little has changed and yet everything has changed. A modern human still prepares food over a heat source, sleeps in a bed, uses vessels, fabrics, co-operates with others and ritualistically buries the dead. Except that some processes are automated and, instead of being made in the hut next door, fabric or cooking vessels are sometimes made a very long way from where they are to be used; a symptom of a desire to remove process when attempting to progress in order to make time for more.. ‘important’.. things..

Over a few thousand years, majority nomadism became majority settled communities and over a few hundred years the idea of camping flipped from being an essential life support practice to a leisure activity, although it still remains a necessity for many nomadic or displaced people. During the transition from Mesolithic hunter-gatherer societies to stationary Neolithic communities there was a shift in the most necessary skills required but many essential basic skills remained. Relatively recently all humans had no choice but to be well equipped with basic survival knowledge. To reject the ability to take care of ourselves is also to gradually change the way we inhabit and relate to the landscape.

There are always new proposals for ways to get outdoors: new gadgets for the fearful, lighter weight equipment for feeble home birds, ‘glamping’. A survival expert leads groups of people through the wilderness to teach them how to live outside in the forest. He guides them into the woods explaining techniques to light fires and construct shelters from branches, like a guru he endows his followers with a realisation: That they already understand these things, they reconnect with some primitive inclinations. He recounts a desire to move tents in the night because the original location didn’t feel right. Sometimes the desire is followed through without an understanding of why, but sometimes he doesn’t know, like a cat eating a plant to feel less sick. Did a part of the brain register a creaking branch which might fall? Was it the lay of the land or the possibility of intruders? Visibility? Buried superstitions rise to the surface and rationality sorts and prioritises them.

Maybe camping is a form of rejection for the seemingly solid structures which contain us and a way to claw back an understanding of the processes which enable our lives. Could a tent and maybe even the associated high-tech gadgets, be a stepping stone, a way to regain some connection with the soil beneath, some faith in senses, instincts and ability, and to re-assess value systems? A tent could be a remedy for despair and apathy, strip back to basics to find a way to experience rawness and to comprehend vulnerability, or a way to experience a sense of independence and self-confidence, or community and co-operation perhaps. Camping, when it is a choice, is one of the tools available to us in the struggle for social and ecological justice.

There Are No Firm Rules - installation view. Collaboration with Glen Stoker, Site Gallery, Sheffield, 2016